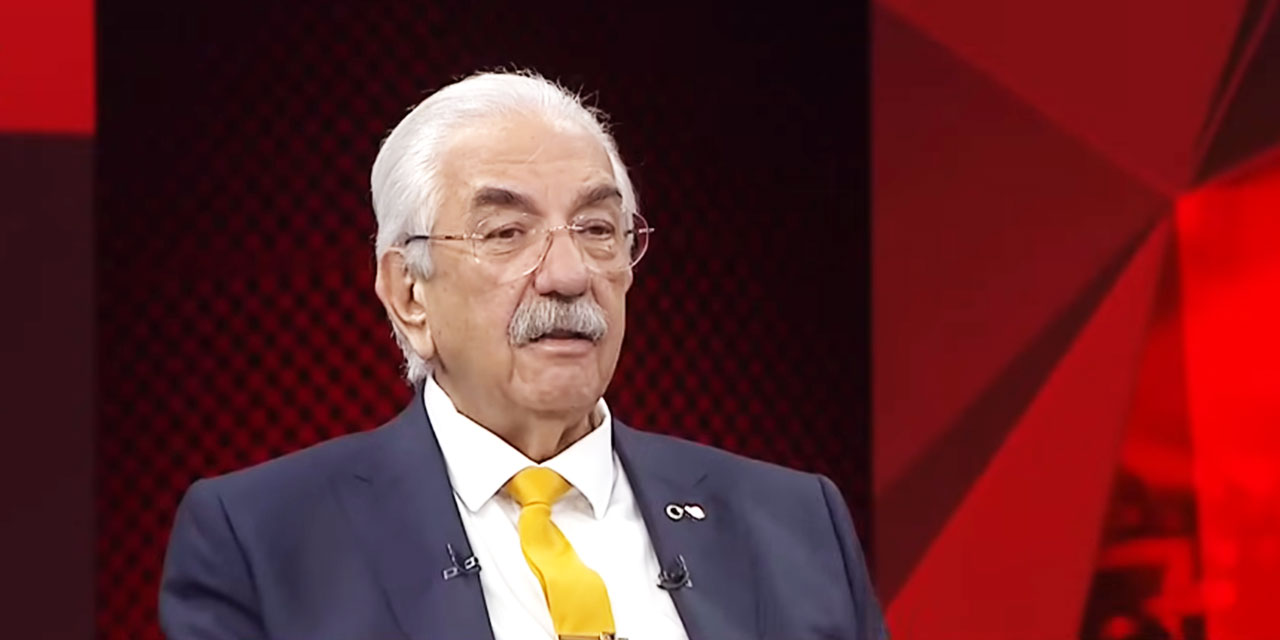

Salahattin ALTUNDAĞ

Mânevî Realizm: “Birinci Söz” Işığında Yeni Bir Bakış Açısı

Realizm Felsefesi, düşündüğümüz veya hissettiğimiz her şeyin -ister somut (örneğin, bir masa veya bir sandalye), ister soyut (örneğin, sevgi veya adâlet gibi kavramlar)- gerçek olduğunu söyler. Buradaki "gerçek"[1] kavramı, bu şeylerin sâdece biz onları düşündüğümüzde veya hissettiğimizde var olmadıklarını, aksine biz farkında olmasak bile var olduklarını ifâde eder.

Diyelim ki bir masa önünüzde duruyor. Siz masayı görüyorsunuz, üzerine dokunabiliyorsunuz ve belki de kokusunu alabiliyorsunuz. Masa, gözlerinizin, ellerinizin ve belki de burnunuzun size söylediği gibi orada, somut ve gerçek bir varlık. Realizm Felsefesi de işte tam olarak bunu ifâde eder: Masanın var olduğu ve sizin tarafınızdan algılanabildiği gerçeğini kabûl eder.

Realistlere göre, siz odadan çıktığınızda da masa orada olmaya devâm eder. Yâni, masanın varlığı sizin onu algılamanıza veya onunla etkileşimde bulunmanıza bağlı değildir. Masa nesnel bir gerçekliktir ve bu nesnel gerçeklik sizin bireysel deneyiminizden veya algınızdan bağımsızdır.

Benzer şekilde, sevgi veya adâlet gibi soyut kavramlar da gerçektirler. Onları hissettiğimizde veya düşündüğümüzde var olduklarını biliyoruz. Biz onları düşünmeyi bıraktığımızda veya hissetmeyi bıraktığımızda da bu kavramlar hâlâ var olmaya devâm ederler. Onların gerçekliği, bizim onları algılamamıza veya farkında olmamıza bağlı değildir.

Bu durum, Realizm Felsefesi'nin en önemli ilkelerinden biridir: Gerçeklik nesneldir ve bu gerçeklik bireysel algıdan bağımsız olarak var olur. Yâni, gerçekler ve doğrular bizim dışımızda, kendi başına var olan ve bizim algılarımızdan bağımsız olan varlıklardır.

Bu basit masa örnek, Realizm Felsefesi'nin temel prensiplerini daha somut ve anlaşılır bir şekilde ifâde eder.

Bedîüzzamân Said Nûrsî'nin “Birinci Söz” eserinde, gerçekliği, insanın içsel dünyâsıyla ilişkilendiren bir anlayışa işâret ettiği görülür. Bir sporcu düşünün, yarışma öncesi bir ritüel uyguluyor: Kendi kendine "Bunu yapabilirim" diye telkinde bulunuyor. Bu telkin, sporcu için algılanabilir ve anlaşılabilir bir gerçekliktir. Ona güç verir, motive eder ve performansını etkiler. Bu telkinin gücü, Realizm Felsefesi'nin bir yansımasıdır. Çünkü bu telkin, sporcunun içsel dünyâsında gerçek bir etki oluşturur ve bu etki, dış dünyâda algılanabilir sonuçlara yol açar.

Nûrsî'nin “Bismillâh” kelimesine atfettiği anlâm, bu örnekteki telkinle benzerdir. “Bismillâh” kelimesi, bir Müslümân için algılanabilir ve anlaşılabilir bir gerçekliktir. Ona güç verir, direnç sağlar ve hayâtındaki eylemleri etkiler. Bu kelime, bireyin içsel dünyâsında gerçek bir etki meydana getirir ve bu etki, dış dünyâda algılanabilir sonuçlara yol açar. Bu durum, Realizm Felsefesi'nin temel prensiplerinden birini yansıtır: Var olan her şey, algılanabilir ve anlaşılabilir bir gerçekliktir.

Başka bir örnek verelim, bir sanatçının bir eser oluşturma sürecini düşünün. Sanatçı, eserini oluştururken genellikle içsel dünyâsından beslenir. Ressamın çizdiği dağ, karlar ve ağaçlar, Allâh'ın meydana getirdiği gerçekliklerdir ve bu oluşturulanlar aracılığıyla Allâh'ın varlığını, yâni gerçekliğin mutlak kaynağını kabûl ederiz. Onun duyguları, düşünceleri, deneyimleri, algıları eserine yansır. Bu içsel dünyânın bir yansıması olan eser, dış dünyâda somut, algılanabilir ve anlaşılabilir bir gerçekliğe dönüşür. İşte bu süreç, "Bismillâh her hayrın başıdır" ifâdesinin somutlaştığı bir örnektir.

Sanatçının içsel dünyâsında bir hareket başlatır ve bu hareket, dış dünyâda algılanabilir ve anlaşılabilir bir eser olarak gerçekleşir. Bu süreç, Realizm Felsefesi'nin bir yansımasıdır çünkü içsel dünyâdaki bir düşünce, dış dünyâda somut bir gerçeklik hâline gelir.

"Bismillâh her hayrın başıdır" sözüyle Nûrsî, her iyi işin “Bismillâh” yâni "Allâh'ın adıyla" başlaması gerektiğini ifâde eder. Bu, Realizm Felsefesi'nin bir yönüne işâret eder. Realizm, dünyâ üzerindeki tüm varlıkların bir gerçekliğinin olduğunu kabûl eder. Bu gerçeklik algılanabilir ve anlaşılabilir bir niteliğe sâhip olabilir. Nûrsî'nin bu ifâdesi, gerçekliğin tek bir mutlak kaynaktan -yani Allâh'tan- geldiğini ifâde eder. Bu yüzden tüm iyi eylemler, bu gerçekliği kabûl eder ve onun adıyla başlar.

Bir ressamı düşünün. Ressam, tuvaline bir dağ manzarası çizmeye başlıyor. Dağın tepesine karlar yağmış, etrafında ise yeşil ağaçlar var. Bu durumu Realizm Felsefesi'ne göre ele alırsak; ressamın çizdiği dağ, karlar ve ağaçlar gerçekliğin birer parçasıdır. Yâni, bu varlıklar maddî dünyâda mevcût olup, algılanabilir ve anlaşılabilirler.

Peki, bu durumu Bedîüzzamân Said Nûrsî'nin “Birinci Söz” kısmındaki ifâdeye nasıl bağlayabiliriz? "Bismillâh her hayrın başıdır" sözüyle Nûrsî'nin ifâde ettiği gibi, her şeyin başı Allâh'tır. Yâni, bu gerçekliklerin kaynağı Allâh'tır. Ressamın çizdiği dağ, karlar ve ağaçlar, Allâh'ın yarattığı gerçekliklerdir ve bu yaratılanlar aracılığıyla Allâh'ın varlığını, yâni gerçekliğin mutlak kaynağını kabûl ederiz.

Ayrıca, Nûrsî'nin "Bismillâh ne büyük, tükenmez bir kuvvet, ne çok, bitmez bir bereket olduğunu anlamak istersen, şu temsîlî hikâyeciğe bak, dinle" ifâdesi de Realizm Felsefesi ile bağdaşır. Nûrsî burada, gerçekliğin -Allâh'ın adının- ne denli büyük bir güç ve bereket olduğunu anlatmak için hikâyeye başvuruyor. Yâni, bir nevi var olan gerçekliği anlamak ve algılamak için hikâyenin bir araç olduğunu belirtiyor. Bu, Realizm Felsefesi'nin gerçekliğin var olduğunu ve anlaşılabileceğini vurgulayan yaklaşımıyla paralel bir durumdur.

Hikâyelendirme hem edebiyât hem de felsefe için güçlü bir araçtır. Hikâyeler, karmaşık düşünceleri, kavramları ve felsefeleri anlaşılır ve erişilebilir hâle getirebilir. Dahası, hikâyeler genellikle insan deneyimine dokunur ve bu da okuyucuların veya dinleyicilerin kendilerini içerikle bağlantı kurarak empati[2] yapmalarını sağlar.

Nûrsî'nin "Bismillâh ne büyük, tükenmez bir kuvvet, ne çok, bitmez bir bereket olduğunu anlamak istersen, şu temsîlî hikâyeciğe bak, dinle" ifâdesinde olduğu gibi, hikâyenin bir araç olarak kullanılması, genellikle somut ve algılanabilir bir gerçeklik oluşturur. Bu, Realizm Felsefesi'ne paralel bir yaklaşımdır çünkü realizm, gerçekliğin algılanabilir ve anlaşılabilir olduğunu öne sürer.

Hikâyenin bu örneğinde, Nûrsî, bir kabile reisinin ismini almanın gücünü ve bereketini anlatmak için bir bedevînin hikâyesini kullanıyor. Bu hikâye, gerçekliğin gücünü ve bereketini somutlaştırarak ve bireyin günlük yaşamında nasıl bir etki ortaya koyabileceğini göstererek, abstract[3] (soyut) bir kavramı - yâni "gerçekliği" - anlaşılır hâle getirir.

Bu şekilde, hikâyenin gücü, karmaşık ve soyut kavramları somutlaştırmak ve gerçek dünyâda nasıl bir etki ortaya çıkarabileceğini göstermek için kullanılır. Bu nedenle, hikâyeler, realizmin sunduğu gerçekliği anlamak ve algılamak için çok değerli araçlar olabilir.

“Bedevî Arap çöllerinde seyahât eden adama gerektir ki, bir kabile reisinin ismini alsın ve himâyesine girsin—tâ şakîlerin şerrinden kurtulup hâcâtını tedârik edebilsin. Yoksa, tek başıyla, hadsiz düşmân ve ihtiyâcatına karşı perişân olacaktır. İşte, böyle bir seyahât için, iki adam sahrâya çıkıp gidiyorlar. Onlardan birisi mütevâzi idi, diğeri mağrur. Mütevâzii, bir reisin ismini aldı; mağrur almadı. Alanı her yerde selâmetle gezdi. Bir kàtıu't-tarîke rast gelse, der: ‘Ben filân reisin ismiyle gezerim.’ Şakî def olur gider, ilişemez. Bir çadıra girse o nâm ile hürmet görür. Öteki mağrur, bütün seyahâtinde öyle belâlar çeker ki, tarif edilmez. Dâima titrer, dâima dilencilik ederdi. Hem zelil hem rezil oldu.”

Bedîüzzamân Said Nûrsî'nin Risâle-i Nûr Külliyatı'ndan "Sözler" adlı şâheserinde yer alan bu hikâye, Realizm Felsefesi'nin bir çerçevesini sunuyor. Hikâye, bir çölde seyahât eden iki bedevînin durumunu anlatır. Hikâyede, mütevâzi olan bedevînin bir kabile reisinin adını alarak seyahât ettiği ve böylece seyahâti boyunca güvende olduğu, mağrur bedevînin ise bir reisin adını almadığı ve bu yüzden seyahâti boyunca zorluklarla karşılaştığı anlatılır.

Bu hikâye, Realizm Felsefesi'ne bir ışık tutuyor. Realizm, var olan her şeyin gerçek olduğunu ve bu gerçekliğin bireysel algıları aşan bir varlık olduğunu ifâde eder. Hikâyede, mütevâzi bedevînin bir kabile reisinin adını alarak seyahât etmesi, gerçekliğin algılanabilir ve anlaşılabilir olduğunu gösteriyor. Bu bedevînin gerçekliği, reisin adını alarak ve bu adın sağladığı güveni kabûl ederek, somutlaşır.

Öte yandan, mağrur bedevî, kabile reisinin adını almayı reddederek, kendi algıladığı gerçeklikten uzaklaşır. Bu gerçeklik, yalnızca bedevînin kendi içsel algılarıyla sınırlıdır ve bu yüzden o, çevresindeki gerçek dünyâyı algılamada başarısız olur. Realizm Felsefesi'ne göre, bu bedevînin gerçekliği, kabile reisinin adının gücünü ve korumasını reddettiği için tamamlanmamıştır.

Bedîüzzamân Said Nûrsî'nin çöl yolculuğu örneğinde, gerçekliğin ve kavramsal gerçekliğin[4] varlığına dikkat çeken benzersiz bir yaklaşım bulunmaktadır.

Bu örnek, çölde yolculuk eden iki adamın hikâyesi üzerinden felsefî bir gerçekliği inceliyor. Bunlardan biri, bir kabile reisinin adını (Bismillâh'ın temsil ettiği gerçeklik) alarak yolculuğuna devâm eder ve bu sâyede güvenli bir şekilde seyahât eder. Diğer adam ise bu adımı atmayı reddeder ve sonuç olarak çeşitli zorluklarla karşı karşıya kalır.

Bu öykü, gerçekliği kabûllenmenin ve onunla uyum içinde yaşamanın önemini vurguluyor. Kendi başına bir güç ve kurtuluş kaynağı olarak görülen "gerçeklik", bu hikâye bağlamında bir kabile reisinin adıyla temsil edilmiştir. Nûrsî, gerçekliği ve onun bireyin hayâtındaki etkisini, bu iki karakter üzerinden somutlaştırır.

Realizm Felsefesi'ne dönersek, Nûrsî'nin bu metni, dünyânın algıdan bağımsız bir gerçeklik olduğu fikrini destekler. Mütevâzi adamın kabile reisinin adını kabûl etmesi ve onun koruması altına girmesi, gerçekliğin (Bismillâh'ın) kabûl edilmesi ve hayâta uygulanması olarak yorumlanabilir. Mağrur adamın zorluklarla karşılaşması ise, gerçekliğin reddedilmesinin ve görmezden gelinmesinin sonuçlarını gösterir.

Bedîüzzamân Said Nûrsî'nin bu ifâdesi, Realizm Felsefesi'nin önemli bir örneğidir. Metin, gerçekliğin kabûl edilmesi ve hayâtın bir parçası hâline getirilmesinin bireyin hayâtında nasıl olumlu bir etki yapabileceğini açıkça gösterir. Bu yaklaşım, gerçekliğin algıdan bağımsız bir varlık olduğunu ve kabûl edilerek bireyin hayâtının iyileştirilebileceğini savunan Realizm Felsefesi'ne uygundur.

Bedîüzzamân, “Bismillâh” ifâdesini sâdece bir kelime olmaktan öte, bir tavrın, bir niyetin ve bir mânevî duruşun ifâdesi olarak görür. “Bismillâh” ifâdesi, sâdece dil ile söylenen bir kelime olmaktan çok daha fazlasını ifâde eder. İslâm inancında, bu ifâde aynı zamânda bir niyetin ve bir mânevî eylemin başlangıcını da belirler.

“Bismillâh” ifâdesini kullanan bir kişi, bu eylemle sâdece Allâh'ın adını anmaz, aynı zamânda Allâh'ın kudretine, bilgisine, hikmetine ve merhametine güvendiğini ve her türlü eylemini ve niyetini Allâh'ın rızâsına uygun olarak gerçekleştirmeyi amaçladığını ifâde eder. Yâni bu ifâde, bir kişinin tüm eylemlerinin ve niyetlerinin Allâh'ın irâdesine ve kanûnlarına tâbi olduğunu kabûl ettiği anlâmına gelir.

Bedîüzzamân'ın çöl örneğini “Bismillâh” ifâdesinin anlâmını açıklamak için kullanması, bu ifâdenin sâdece sözsel bir ifâde olmadığını, aynı zamânda bir tavrın ve bir duruşun ifâdesi olduğunu gösterir. Bedevî, çölde seyahât ederken, bir kabile reisinin adını kullanarak koruma ve yardım talep eder. Bu durum, “Bismillâh” ifâdesini kullanan bir kişinin, Allâh'ın adını anarak ve O'nun himâyesine girdiğini ifâde eder. Artık onun rızâsı dâiresinde hareket edecektir. Yoksa kabile reisi onu kabûl etmeyecektir.

Dolâyısıyla, “Bismillâh” ifâdesi, sâdece dil ile söylenen bir kelime olmaktan öte, bir kişinin mânevî duruşunu ve niyetini ifâde eder. Bu ifâde, bir kişinin hayâtındaki tüm eylemlerinin ve niyetlerinin Allâh'ın rızâsına ve kanûnlarına uygun olarak gerçekleştirilmesi anlâmına gelir. Ve bu durum, aynı zamânda, kişinin mânevî gücünü ve kendine olan güvenini artırır ve hayâtındaki zorlukları aşmasına yardımcı olur.

"O'nun himâyesine girmek" ifâdesi Allâh'ın istediği ve razı olduğu şekilde yaşamayı, O'nun belirlediği ahlakî ve etik kurallara uymayı ve yaşam tarzını sürdürmeyi ifâde eder. Bu, kişinin eylemlerini, düşüncelerini ve niyetlerini Allâh'ın irâdesine, hikmetine ve kanûnlarına uygun olarak düzenlemesi anlâmına gelir.

Bu ifâde aynı zamânda, kişinin hayâtının her yönünü Allâh'ın rızâsı doğrultusunda yönlendirmeyi, O'na teslim olmayı ve O'nun yolunda ilerlemeyi ifâde eder. Bu, aynı zamânda Allâh'ın koruması, yardımı ve rehberliği altında olduğunu kabûl etmeyi ve O'na olan güveni ifâde eder.

“Bismillâh” demek, bu teslimiyeti ve güveni ifâde eder. Kişi bu ifâde ile Allâh'ın adını anar ve her türlü işine O'nun adıyla başlar. Bu da kişinin eylemlerinin ve niyetlerinin Allâh'ın irâdesine ve kanûnlarına uygun olduğunu, O'nun himâyesi altında olduğunu ve O'nun rehberliğine ve yardımına ihtiyâç duyduğunu ifâde eder.

Dolâyısıyla, "O'nun himâyesine girmek", hem mânevî bir koruma ve yardım ifâde eder, hem de kişinin Allâh'ın irâdesine ve kanûnlarına uygun bir yaşam sürdürme niyetini ifâde eder. Bu durum, aynı zamânda kişinin hayâtının her yönünü Allâh'ın rızâsı doğrultusunda yönlendirme niyetini ve O'na olan güvenini ifâde eder. Bu niyet ve güven, kişiye iç huzur, mânevî güç ve yaşamındaki zorlukları aşma kabiliyeti sağlar.

“Bismillâh” ifâdesinin ve genel olarak İslâmî inancın getirdiği bu perspektif, realizm felsefesinden farklı bir gerçeklik anlayışı sunar. Bu perspektifte, gerçeklik sâdece dış dünyâdaki objektif olâylar ve nesnelerle sınırlı değildir; aynı zamânda bizim niyetlerimiz, inançlarımız ve eylemlerimiz tarafından da şekillendirilir.

"Allâh'ın adıyla" demek veya "O'nun himâyesine girmek" ifâdeleri, gerçekliğin sâdece dış dünyâdaki objektif nesneler ve olâylarla sınırlı olmadığını, aynı zamânda bizim inançlarımız, niyetlerimiz ve eylemlerimiz tarafından da belirlendiğini gösterir. Bu, realizmin genel olarak kabûl ettiği "objektif gerçeklik"[5] anlayışından daha geniş ve daha derin bir gerçeklik anlayışını içerir.

Örneğin, “Bismillâh” demek, sâdece bir kelimeyi söylemekten çok daha fazlasını ifâde eder: Bu, kişinin niyetlerini, inançlarını ve eylemlerini Allâh'ın irâdesine, hikmetine ve kanûnlarına uygun olarak düzenlediğini ve bu şekilde hayâtını sürdürdüğünü ifâde eder. Bu, dış dünyânın objektif gerçekliği ile kişinin iç dünyâsındaki inançları, niyetleri ve eylemleri arasında bir köprü kurar ve böylece daha derin ve daha geniş bir gerçeklik anlayışını ortaya koyar.

Bu nedenle, İslâmî inanç ve realizm felsefesi arasında hem benzerlikler hem de farklılıklar vardır. Her ikisi de gerçekliğin var olduğunu kabûl eder, ancak gerçekliğin ne olduğu ve nasıl anlaşılması gerektiği konusunda farklı görüşlere sâhiptirler. Realizm genellikle dış dünyâdaki objektif gerçekliğe odaklanırken, Bedîüzzamân Said Nûrsî'nin düşüncesi ve dolâyısıyla İslâmî inanç hem dış dünyâdaki objektif gerçekliği hem de iç dünyâmızdaki inançları, niyetleri ve eylemleri içeren daha geniş ve daha derin bir gerçeklik anlayışını sunar.

“İşte, ey mağrur nefsim, sen o seyyâhsın. Şu dünyâ ise bir çöldür. Aczin, fakrın hadsizdir. Düşmânın, hâcâtın nihâyetsizdir. Madem öyledir; şu sahrânın Mâlik-i Ebedî ve Hâkim-i Ezelîsinin ismini al. Tâ bütün kâinatın dilenciliğinden ve her hâdisâtın karşısında titremeden kurtulasın.”

Bu ifâde hem derin bir mânevî anlayışı hem de geniş bir varoluşçu bakış açısını yansıtır. Öte yandan, Realizm felsefesi, gerçekliğin objektifliğini ve düşüncelerimizden bağımsız olarak var olduğunu savunur. Bu iki görüş, ilk bakışta birbirinden ayrı gibi görünebilir. Ancak, detâylı bir inceleme, bu iki bakış açısı arasındaki ilginç karşılaştırmaları ve karşıtlıkları ortaya çıkarır.

Nûrsî'nin metninde, dünyâ bir çöl olarak betimlenir[6] ve bu çölde gezinen bizlerin aczimiz, fakrımız, düşmânlarımız ve ihtiyâçlarımızın nihâyetsiz olduğu vurgulanır. Bu, hayâtın zorluklarını ve belirsizliklerini, içinde bulunduğumuz dünyânın karmaşıklığını ve belirsizliğini anlatır. Bu durum, realizmin dış dünyânın varlığını ve objektif gerçekliğini kabûl eden temel öğretileri ile uyuşmaktadır.

Bununla birlikte, Nûrsî'nin yaklaşımı, bu çölde -yani dünyâda- hayâtta kalabilmek ve zorluklarla başa çıkabilmek için "Mâlik-i Ebedî ve Hâkim-i Ezelîsinin ismini al" yâni "Allâh'ın adıyla hareket et" çağrısında bulunur. Burada, gerçeklik sâdece objektif bir varoluş olan "çöl" ile sınırlı değildir; aynı zamânda Allâh'ın irâdesine, hikmetine ve kanûnlarına uygun olarak düzenlenen bir yaşamı da içerir.

Bu, realizm felsefesinin genellikle savunduğu objektif gerçeklik anlayışından daha geniş ve daha derin bir gerçeklik anlayışını temsil eder. Bu yaklaşımda, gerçeklik sâdece dış dünyâda değil, aynı zamânda bizim iç dünyâmızda da bulunur - inançlarımız, niyetlerimiz, eylemlerimiz ve Allâh'a olan bağlılığımız.

Nûrsî'nin “Birinci Söz” metnindeki bu görüş, realizm felsefesinin dış dünyânın objektif gerçekliğine odaklanma eğilimine zengin bir içsel ve mânevî boyut ekler. Bu, sâdece algılanabilir ve ölçülebilir olanın ötesinde, mânevî ve içsel gerçekliğin de önemli bir yeri olduğunu hatırlatır.

Sonuç olarak, Bedîüzzamân Said Nûrsî'nin “Birinci Söz” metni ve realizm felsefesi, gerçeklik konusunda farklı bakış açıları sunar. Her ikisi de gerçekliğin karmaşıklığını ve çok boyutluluğunu kabûl eder, ancak Nûrsî, dış dünyânın objektif gerçekliği ile iç dünyâmızın mânevî ve moral gerçekliği arasında bir bağ kurarak, realizm felsefesinin genellikle üzerinde durmadığı bir boyutu öne çıkarır. Bu, hayâtın zorlukları ve belirsizlikleri ile başa çıkmanın sâdece dış dünyâyı anlamakla sınırlı olmadığını, aynı zamânda iç dünyâmızı ve mânevî gerçeklikleri de kucaklamayı gerektirdiğini hatırlatır.

METNİN İNGİLİZCESİ

SPIRITUAL REALISM: A NEW PERSPECTIVE THROUGH THE LENS OF THE “First Word”

The Philosophy of Realism asserts that everything we think or feel – whether it's tangible (such as a table or chair) or intangible (like concepts of love or justice) – is real. Herein, the term "real"[7] signifies that these entities do not solely exist when we think about or feel them, rather, they persist even when we are unaware of them.

Consider the scenario of a table standing before you. You see the table, you can touch it, and perhaps you can even smell it. The table is there, as a physical and palpable entity, just as your eyes, hands, and possibly your nose relay to you. This is precisely what the Philosophy of Realism articulates: it acknowledges the existence of the table and the fact that it can be perceived by you.

According to Realists, even when you exit the room, the table continues to exist. In other words, the existence of the table is not contingent upon your perception or interaction with it. The table is an objective reality, and this objective reality is independent of your individual experience or perception.

Similarly, abstract concepts such as love or justice are also real. We know they exist when we feel or think about them. Even when we stop thinking about or feeling these concepts, they continue to exist. Their reality is not dependent on our perception or awareness of them.

This is one of the most critical principles of the Philosophy of Realism: Reality is objective and this reality exists independent of individual perception. That is to say, facts and truths are entities that exist outside of us, autonomously and independent of our perceptions.

This simple table example articulates the foundational principles of the Philosophy of Realism in a more concrete and comprehensible manner.

In the “First Word” by Bediuzzaman Said Nursi, we observe a conception that associates reality with the inner world of the individual. Consider an athlete who performs a ritual before a competition: self-affirming, "I can do this." This affirmation constitutes a perceptible and understandable reality for the athlete. It empowers them, motivates them, and influences their performance. The power of this affirmation is a reflection of the Philosophy of Realism. For this affirmation creates a genuine impact in the athlete's inner world, and this impact leads to perceivable outcomes in the external world.

The meaning Nursi attributes to the word “Bismillah” parallels the affirmation in the aforementioned example. The word “Bismillah” serves as a perceptible and understandable reality for a Muslim. It provides strength, fosters resilience, and influences actions in their life. This word engenders a genuine impact in the individual's inner world, and this impact manifests as perceptible outcomes in the external world. This scenario mirrors one of the fundamental principles of the Philosophy of Realism: everything that exists constitutes a perceptible and understandable reality.

With the phrase, "Bismillah is the beginning of all goodness" Nursi signifies that all good deeds ought to commence with “Bismillah” or "in the name of Allah." This points towards an aspect of the Philosophy of Realism. Realism acknowledges the reality of all entities in the world. This reality can possess a perceivable and comprehensible attribute. Nursi's expression denotes that the reality emanates from a single, absolute source - Allah. Therefore, all virtuous actions commence by accepting this reality and in His name.

Consider a painter. The painter begins to illustrate a mountainous landscape on their canvas. Snow caps the mountain, surrounded by verdant trees. If we examine this scenario from the perspective of the Philosophy of Realism, the mountain, snow, and trees that the painter sketches are components of reality. That is, these entities exist in the material world and are perceivable and understandable.

How can we connect this situation to the statement in the “First Word” section by Bediuzzaman Said Nursi? As Nursi expressed with the phrase "Bismillah is the beginning of all goodness" the origin of everything is Allah. Hence, the source of these realities is Allah. The mountain, snow, and trees drawn by the painter are realities created by Allah, and through these creations, we acknowledge the existence of Allah, the absolute source of reality.

Additionally, Nursi's statement, "If you wish to understand what a great, inexhaustible power 'Bismillah' possesses, what an immense, never-ending blessing it is, consider and listen to this illustrative story" aligns with the Philosophy of Realism. In this context, Nursi resorts to storytelling to convey the profound power and blessing that reality - in the name of Allah - encompasses. Essentially, he underlines the use of a story as a tool for understanding and perceiving existing reality, which parallels the Philosophy of Realism's emphasis on the existence and comprehensibility of reality.

Storytelling is a potent instrument in both literature and philosophy. Stories can render complex ideas, concepts, and philosophies understandable and accessible. Furthermore, stories typically touch upon human experiences, thereby enabling readers or listeners to empathize[8] and connect with the content.

As seen in Nursi's statement, "If you wish to understand what a great, inexhaustible power 'Bismillah' possesses, what an immense, never-ending blessing it is, consider and listen to this illustrative story", the utilization of a story often generates a tangible and perceivable reality. This approach aligns with the Philosophy of Realism, as realism advocates for reality being perceivable and comprehensible.

In this instance of storytelling, Nursi employs the tale of a Bedouin to delineate the power and blessing inherent in assuming the name of a tribal chief. This story renders an abstract concept - "reality" - comprehensible by embodying the power and blessing of reality and demonstrating the impact it can engender in an individual's everyday life.

In this manner, the potency of a story is harnessed to materialize complex and abstract notions, and illustrate the potential effects they can manifest in the real world. Therefore, stories can prove to be invaluable tools for understanding and perceiving the reality offered by realism.

"It is incumbent upon a man journeying in the Bedouin Arabian deserts to adopt the name of a tribal chief and seek his protection—only then can he evade the harm of the marauders and meet his necessities. Otherwise, alone, he will be left distraught, confronting countless enemies and his own needs. For such a journey, two men set forth into the wilderness. One was humble, the other arrogant. The humble one adopted a chieftain's name; the arrogant one did not. The humble one traveled in safety everywhere. Should he encounter a highwayman, he would state, 'I roam under the name of such a chieftain.' The marauder would retreat, unable to harm him. Entering a tent, he would receive respect because of the name. The other, the arrogant one, throughout his journey, endured such calamities that they are beyond description. He was constantly in fear and constantly begging. He became both pitiful and disgraceful."

This narrative, drawn from "The Words," a masterpiece in Bediuzzaman Said Nursi's collection, the Risale-i Nur, provides a framework for the Philosophy of Realism. The story depicts the situation of two Bedouins journeying through a desert. The narrative describes how the humble Bedouin adopted a tribal chief's name and consequently maintained his safety throughout the journey, whereas the arrogant Bedouin did not, and therefore confronted hardships.

The story shines a light on the Philosophy of Realism. Realism asserts that everything that exists is real, and this reality transcends individual perceptions. In the story, the humble Bedouin's journey under a chieftain's name demonstrates that reality is perceivable and understandable. The reality of this Bedouin materializes as he accepts the protection offered by the chief's name.

On the other hand, the arrogant Bedouin distances himself from perceived reality by refusing to take the chieftain's name. His reality is confined to his own internal perceptions, leading to his failure to perceive the reality of his surroundings. According to the Philosophy of Realism, this Bedouin's reality is incomplete, as he rejected the power and protection of the tribal chief's name.

In Bediuzzaman Said Nursi's example of the desert journey, there exists a distinctive approach that draws attention to the existence of reality and the concept of truth.

This instance explores a philosophical reality through the narrative of two men journeying in the desert. One of them proceeds with his journey by adopting the name of a tribal chief (representing the reality symbolized by 'Bismillah'), thereby enabling him to travel securely. The other man, however, rejects this step and consequently encounters various adversities.

The story underscores the significance of accepting reality and harmoniously coexisting with it. The "reality," viewed as an independent source of power and salvation, is represented in this narrative context by the name of a tribal chief. Nursi concretizes the reality and its impact on an individual's life through these two characters.

Returning to the Philosophy of Realism, this text by Nursi supports the notion that the world harbors a reality independent of perception. The humble man's acceptance of the tribal chief's name and his entry under his protection can be interpreted as the acceptance of reality (symbolized by 'Bismillah') and its application to life. The adversities faced by the arrogant man demonstrate the consequences of rejecting and overlooking reality.

This articulation by Bediuzzaman Said Nursi is a significant illustration of the Philosophy of Realism. The text explicitly demonstrates how the acceptance of reality and its integration into life can have a positive impact on an individual's existence. This approach aligns with the Philosophy of Realism, which argues that reality is an entity independent of perception and that accepting it can improve an individual's life.

Bediuzzaman views the expression “Bismillah” as more than just a word; it represents an attitude, an intention, and a spiritual stance. The utterance of “Bismillah” signifies much more than just a word spoken with the tongue. In the Islamic faith, this phrase also marks the inception of an intention and a spiritual action.

A person who utilizes the phrase “Bismillah” not only mentions the name of Allah, but also implicitly expresses trust in Allah's power, knowledge, wisdom, and mercy. Moreover, they intend to perform every action and formulate every intention in accordance with the pleasure of Allah. Thus, this utterance signifies the acknowledgment that all of one's actions and intentions are subordinate to the will and laws of Allah.

The use of a desert example by Bediuzzaman to explain the meaning of “Bismillah” indicates that it is not merely a verbal statement, but also embodies a stance and a posture. The Bedouin, while traveling in the desert, seeks protection and assistance by invoking the name of a tribal chief. This situation symbolizes a person using the phrase “Bismillah” to call upon the name of Allah and enter into His protection. They will now act within the realm of His approval, or else the tribal chief will not accept them.

Hence, the phrase “Bismillah” transcends a word merely spoken with the tongue, reflecting an individual's spiritual position and intention. It signifies that all the actions and intentions in a person's life are executed in accordance with the pleasure and laws of Allah. And this condition, in turn, enhances a person's spiritual power and self-confidence, aiding them in overcoming life's difficulties.

To "enter into His protection" signifies living according to Allah's desires and approval, adhering to the moral and ethical rules He has set, and maintaining the way of life He has designated. This means arranging one's actions, thoughts, and intentions to align with Allah's will, wisdom, and laws.

This phrase also represents the commitment to guide every aspect of one's life in accordance with Allah's pleasure, to surrender to Him, and to progress in His path. It simultaneously signifies acceptance of being under Allah's protection, assistance, and guidance, and expressing trust in Him.

The act of uttering “Bismillah” signifies such submission and trust. With this phrase, the individual invokes the name of Allah and commences every endeavor in His name. This implies that the person's actions and intentions conform to Allah's will and laws, that they are under His protection, and that they require His guidance and assistance.

Consequently, to "enter His protection" signifies both a spiritual protection and assistance, as well as the intent to lead a life in accordance with Allah's will and laws. It simultaneously denotes the intent to guide every aspect of one's life in line with Allah's pleasure and trust in Him. This intent and trust furnish the individual with inner peace, spiritual strength, and the ability to overcome the challenges in life.

This perspective bestowed by the utterance of “Bismillah” and, more broadly, by Islamic belief, introduces a conception of reality that diverges from the philosophy of realism. Within this perspective, reality is not merely limited to the objective events and objects in the external world; it is also shaped by our intentions, beliefs, and actions.

Phrases such as "in the name of Allah" or "enter His protection" underline that reality is not solely bound by the objective objects and events in the external world, but it is also determined by our beliefs, intentions, and actions. This represents a broader and deeper understanding of reality than the "objective reality" generally accepted by realism.

For instance, uttering “Bismillah” signifies much more than merely pronouncing a word: it represents the organization of one's intentions, beliefs, and actions in accordance with Allah's will, wisdom, and laws, and thus leading their life. This establishes a bridge between the objective reality of the external world and the beliefs, intentions, and actions within the individual's internal world, thereby revealing a deeper and broader understanding of reality.

Hence, there exist both similarities and differences between Islamic belief and the philosophy of realism. Both accept the existence of reality, yet hold divergent views on what reality constitutes and how it should be comprehended. While realism typically focuses on the objective reality in the external world, the thought of Bediuzzaman Said Nursi, and thereby Islamic belief, proposes a broader and deeper understanding of reality that encompasses not only the objective reality of the external world but also the beliefs, intentions, and actions within our internal world.

"Behold, O arrogant self, you are that traveler. This world is a desert. Your weakness and poverty are boundless. Your enemies, your needs are endless. Since this is so, take the name of the Eternal Owner and the Everlasting Judge of this desert. So that you may be freed from the begging of the whole universe and trembling in the face of every incident."

This expression reflects both a profound spiritual understanding and a broad existential perspective. On the other hand, the philosophy of realism asserts the objectivity of reality and its existence independent of our thoughts. These two viewpoints might appear disparate at first glance. However, a detailed examination reveals intriguing comparisons and contrasts between these two perspectives.

In Nursi's text, the world is depicted as a desert, and it is emphasized that our impotence, poverty, enemies, and needs within this desert are endless. This conveys the hardships and uncertainties of life, the complexity and unpredictability of the world we inhabit. This situation is congruent with the fundamental teachings of realism, which accept the existence of the external world and its objective reality.

Nevertheless, Nursi's approach implores to "take the name of the Eternal Owner and Everlasting Judge" in this desert - that is, in the world - to survive and to cope with difficulties, which is to say, "act in the name of Allah". Here, reality is not confined to the "desert", an objective existence; it also encompasses a life arranged in accordance with Allah's will, wisdom, and laws.

This represents a broader and deeper understanding of reality than the objective reality typically advocated by the philosophy of realism. In this approach, reality is found not just in the external world but also within our internal world - in our beliefs, intentions, actions, and dedication to Allah.

This viewpoint in Nursi's “First Word” text adds a rich inner and spiritual dimension to the tendency of the philosophy of realism to focus on the objective reality of the external world. It serves as a reminder that the spiritual and internal reality also holds significant ground beyond what is perceptible and measurable.

In conclusion, both Bediuzzaman Said Nursi's “First Word” text and the philosophy of realism present different perspectives on reality. Both accept the complexity and multi-dimensionality of reality, but Nursi highlights a dimension that realism typically overlooks by establishing a connection between the objective reality of the external world and the spiritual and moral reality within our internal world. This is a reminder that coping with the hardships and uncertainties of life is not limited to understanding the external world; it also necessitates embracing our internal world and spiritual realities.

[1] Gerçek: Realist felsefede ifade edilen “gerçek” kavramı, insan zihninden bağımsız olarak var olan bir varlık veya realiteyi anlatır. Realizm, gerçeğin bilgisinin duyu organları, gözlem ve deneylerle elde edilebileceğini ileri sürer. Realizm, değerlerin de toplumun kendisinde bulunduğunu kabûl eder.

[2] Empati: Başka bir kişinin duygu, düşünce ve deneyimlerini anlama ve paylaşma yeteneği olarak tanımlanabilir. Empati kurmak, iletişimi geliştirmeye, çatışmaları çözmeye ve ilişkileri güçlendirmeye yardımcı olur. Empati, sadece başkalarının ne hissettiğini bilmek değil, aynı zamanda onlara karşı anlayışlı ve destekleyici olmak demektir.

[3] Abstract: Soyut veya özet anlamına gelir. Bir şeyin abstract olması, gerçek veya somut olmadığı anlamına gelir. Örneğin, bir sanat eserinin abstract olması, gerçekçi bir şekilde resmedilmemiş olduğu anlamına gelir. Bir metnin abstract olması ise, metnin ana fikrini veya amacını kısaca özetlediği anlamına gelir.

[4] Kavramsal Gerçeklik: Realizmin farklı türlerine göre değişebilir. Ancak genel olarak, realizm, kavramların veya evrensel kategorilerin varlığını kabul eden bir felsefi akımdır. Realizme göre, kavramlar, gerçekliğin bir parçasıdır ve insan zihninden bağımsız olarak var olurlar. Örneğin, "kırmızı" kavramı, kırmızı renkli nesnelerin ortak bir özelliğini ifade eder ve bu özellik, insanlar tarafından algılanmasa bile gerçekliğin bir yönüdür. Kavramsal gerçek, realizmin bu görüşünü yansıtan bir terimdir. Kavramsal gerçek, kavramların gerçekliğe sâhip olduğunu ve insan zihninin sâdece onları tanımlamak için kullandığını belirtir.

[5] Objektif Gerçeklik: Sanatçının gözlemlediği dünyayı olduğu gibi yansıtmaya çalışmasıdır. Realist sanatçılar, toplumsal, siyasal ve kültürel koşulları göz ardı etmeden, insanların yaşamını ve çevresini betimlerler. Realizm, romantizmin aksine, hayâl gücüne veya duygulara değil, akla ve deneyime dayanan bir sanat anlayışıdır.

[6] Betimlemek: Bir nesne, kişi, olay veya durumu sözcüklerle anlatmak, tasvîr etmek demektir. Betimleme, edebiyâtın önemli bir sanatıdır. Betimleme yaparken, duyulara hitâp eden ayrıntılar kullanmak gerekir. Betimleme, okuyucunun hayâl gücünü zenginleştirir ve metne canlılık katar.

[7] Reality: In realist philosophy, the term "reality" refers to an entity or reality that exists independent of the human mind. Realism posits that knowledge of reality can be attained through sensory organs, observation, and experiments. Realism also accepts that values reside within society itself.

[8] Empathy: Can be defined as the ability to understand and share the feelings, thoughts, and experiences of another person. Establishing empathy aids in enhancing communication, resolving conflicts, and strengthening relationships. Empathy signifies not only knowing what others are feeling but also being understanding and supportive towards them.

Küfür, hakaret, rencide edici cümleler veya imalar, inançlara saldırı içeren, imla kuralları ile yazılmamış,

Türkçe karakter kullanılmayan ve BÜYÜK HARFLERLE yazılmış yorumlar

Adınız kısmına uygun olmayan ve saçma rumuzlar onaylanmamaktadır.

Anlayışınız için teşekkür ederiz.